The Arab Summit held in the Iraqi capital Baghdad took place against the backdrop of escalating regional crises in the Arab world. Nevertheless, its outcomes remained within the traditional framework of previous Arab summits—both in terms of rhetorical formulations and the lack of binding enforcement mechanisms. This pattern reflects the continued institutional approach of the Arab League, with the Arab Summit representing its highest official body.

The Arab League, founded on March 22, 1945, is one of the oldest still-existing regional organizations in the world. In fact, it was established even before the founding of the United Nations, which took place in October of the same year. Remarkably, the League’s charter resembles more closely that of the League of Nations—the predecessor of the UN—than the UN Charter itself. The League primarily focused on maintaining a balance between the political systems of the Arab states and preventing political differences from escalating into open conflicts—whether political, economic, or military—instead of building a unification project or genuine Arab integration in politics and economics.

This balancing orientation clearly shaped the role of the Arab League in the following decades. It developed into an institution aimed at managing differences between member states within a minimum consensus framework, without possessing executive powers that would allow it to overcome disputes or enforce unified decisions. This led to the consolidation of a functional pattern more geared toward crisis containment than resolution, and to maintaining a minimal level of relations between states rather than creating a coherent collective structure, as envisioned by theorists of joint Arab action.

The Founding Conditions of the Arab League

Two currents contributed to the establishment of the Arab League. The first was the influence of the pan-Arab movement, which found support among significant parts of the political and cultural elites as well as among the broader population. This current emerged in the second half of the 19th century as a response to the rise of Turkish nationalism within the Ottoman Empire, which ruled large parts of the Arab world and pursued a policy of “Turkification” of the empire. Added to this was the influence of many Arab intellectuals who called for the promotion of Arab national consciousness, modeled on European national movements.

The pan-Arab movement gained considerable momentum after the official end of the Ottoman Empire in 1924. At the same time, modern political entities began to emerge in the Arab world, such as Iraq (1921), Egypt (partially independent since 1922), Yemen, Syria, and others. With the formation of these nation-states, Arabs began to feel that they were no longer part of a unified Arab entity but now defined themselves through new state identities such as Iraqis, Syrians, or Yemenis. This triggered calls for the creation of an Arab unification state that would bring together the peoples of the region in a shared project.

The second, and far more influential, factor behind the founding of the Arab League lay in the geopolitical changes triggered by World War II—particularly the policies of Britain in the region. British decision-makers sought Arab support for the Allies in the fight against Nazi Germany—especially after the 1941 coup attempt by Rashid Ali al-Gailani in Iraq, which showed pro-German tendencies. These events prompted Britain to reassess its relations with the Arab world.

In 1943, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden declared that his government viewed Arab aspirations for some form of unity or cooperation “with goodwill.” This statement encouraged several Arab states to propose the creation of a regional framework. Egypt and Iraq played a particularly prominent role: while Cairo proposed a limited Arab coordination framework, Baghdad advocated a more comprehensive Arab union. Even though these initiatives were couched in nationalist rhetoric, they fundamentally reflected the interest of the respective regimes in securing their own influence and preserving their national interests more than a genuine desire for Arab unity.

The founding debates of the League were marked by caution and mistrust among some Arab governments. This led to a strong emphasis in the charter on the sovereignty of each member state and its national decision-making autonomy. The powers of the new organization were deliberately limited to prevent it from being used by individual regimes as a tool of influence over others.

Under these balancing conditions, the Arab League was officially established on March 22, 1945, with seven then-independent Arab states as founding members: Egypt, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan (then the Emirate of Transjordan), Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen.

The Influence of Intra-Arab Relations on the Effectiveness of the Arab League

Relations among Arab states have been marked by significant tensions over the past decades—characterized by phases of disagreement and occasional conflict, interrupted by periods of détente and temporary rapprochement. The founding of the Arab League introduced the first outlines of an “official Arab system,” which raised hopes and expectations that existing divisions could be overcome and an institutionalized system of joint cooperation could be established.

However, these ambitions were not realized to the desired extent, as they would have required a gradual development of political systems and a modernization of the administration of Arab affairs—particularly with regard to separating issues of politics, security, and defense on the one hand, from economic, cultural, and social matters on the other. Although some progress was made in these areas, most of these achievements were more responses to external pressure than expressions of genuine political will within the Arab states.

Just as the world experienced ideological division between East and West during the Cold War, the Arab world also suffered from parallel divisions. These were not limited to political orientations but extended to economic and social models as well. Nevertheless, these differences produced no notable positive results: Western-oriented states failed to sustainably establish democratic values and civil liberties, while followers of the Eastern model did not succeed in building stable and productive developmental economies. Ultimately, these ideological and political divisions merely led to the formation of blocs and conflict lines among Arab states—with direct consequences for the effectiveness of the Arab League. Its decision-making and enforcement capabilities were severely limited.

In light of the magnitude of these divisions and the deep differences between the political systems of the Arab states, it is remarkable that the Arab League has managed to persist over such a long period and to secure a minimal level of Arab solidarity as well as the continued existence of the collective official Arab system—which, in itself, can already be considered an achievement.

External Influences on the Effectiveness of the Arab League

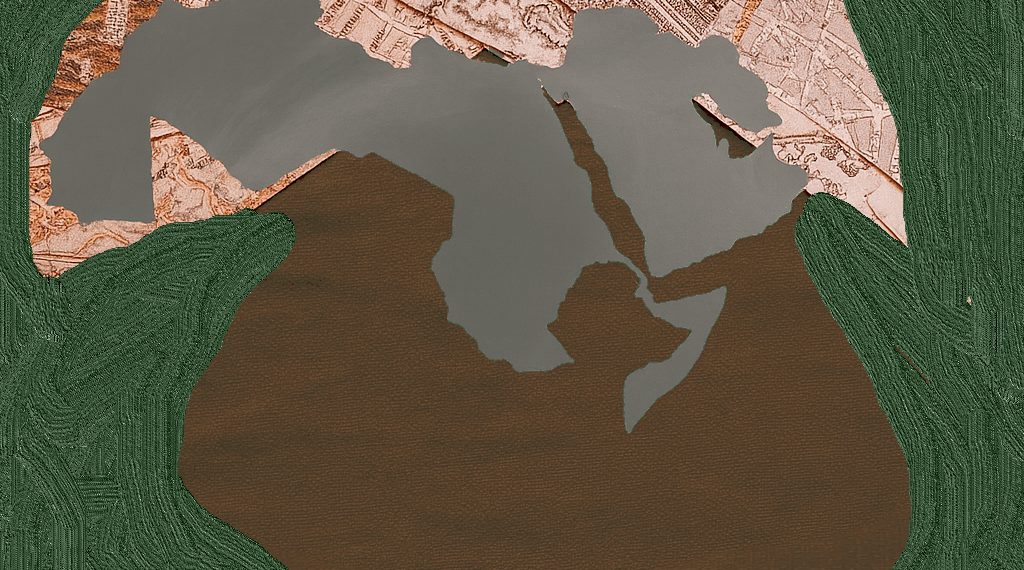

Current global upheavals are a major influence on the dynamics and performance of the Arab regional system. In many respects, these external influences affect the Arab world more profoundly than other regions. This is due to a number of structural and geopolitical factors—chief among them the strategic geographical location of the Arab world, which connects three continents, controls key maritime trade routes, and possesses significant natural resources, particularly oil and gas, which rank among the most important global energy sources.

This location and the associated resources have consistently sustained the interest of international powers in the Arab world—not only in terms of economic cooperation or competition, but also regarding political and security-related influence. The geopolitical sensitivity of the region is further intensified by a series of unresolved crises, such as the Palestinian question and the conflicts in Syria, Yemen, Sudan, and Libya. Many of these conflicts remain without comprehensive and lasting solutions and frequently appear on the agendas of international organizations such as the UN Security Council.

In this context, the institutional structure of the Arab regional system reveals itself to be markedly weak. Its limited capacity for collective crisis management has led to a visible decline in the mechanisms of Arab solidarity and joint action. This weakness has paved the way for increased intervention by international and regional actors in Arab affairs—whether through direct political initiatives or through security and economic alliances with individual states in the region.

It is also noteworthy that some Arab countries have independently established strategic relationships with external powers—as a means to secure their national security or pursue short-term political and economic interests. This has further diminished the effectiveness of collective action within the framework of the Arab League and weakened the central role of a unified Arab decision-making authority.

These complex external challenges, combined with the internal crises facing many Arab states, have significantly impacted the effectiveness of the Arab League. They present the organization with serious tests, requiring a fundamental reassessment of its role, structures, and operational mechanisms in the context of a shifting and increasingly complex international order.

Arab Summits: Key Features

Since the beginning of Arab cooperation to the present day, a total of 34 Arab summits have been held, including 20 regular and 11 extraordinary or non-regular summits. These meetings—whether convened regularly or irregularly—reflect a set of defining characteristics that mark the functioning of this highest regional mechanism. The most important points can be summarized as follows:

First, the Arab-Israeli conflict was a central issue at almost all summits—either as the main reason for convening the summit, such as in direct response to Israeli attacks, or as a recurring agenda item in explicit or implicit form. This underscores the continued central importance of this issue to the priorities of the Arab world.

Second, many of these summits were characterized more by reactive than by proactive stances. They were often convened in response to sudden regional or international developments, rather than being based on forward-looking visions or joint strategic initiatives aimed at anticipating crises or addressing potential risks early on. This reduced the Arab system’s ability to manage or effectively influence events.

Third, the summits often failed to demonstrate the necessary political will to resolve crises fundamentally and comprehensively. Instead, efforts typically focused on crisis management and on containing immediate effects. The discussions were frequently ceremonial in nature, dominated by cautious diplomatic rhetoric. Most summits ended with final communiqués in rhetorical language, emphasizing consensus on general principles while avoiding controversial core issues or softening them with vague formulations.

Fourth, the outcomes of the summits fell short of public expectations. Opinion polls and the general sentiment among large parts of the Arab public showed growing frustration over the lack of tangible achievements that would match the scale of the challenges facing the Arab world. This contributed to a deepening loss of trust between the people and the institutions of Arab cooperation.

Fifth, over time, some summits evolved into symbolic occasions, where political positions were mainly documented or limited moral support was expressed—given the absence of clear implementation mechanisms for the decisions made. Often, the summits contented themselves with the provision of temporary financial aid or declarations of solidarity, without addressing the structural causes of the issues at hand.

Sixth, the effectiveness of these summits has gradually declined over time—with the exception of a few historic milestones that had relatively significant impact. These include:

- The Khartoum Summit in 1967, which, after the defeat in June, formulated the famous “Three No’s” (no peace, no negotiations, no recognition),

- The Algiers Summit in 1973, following the October War,

- The Rabat Summit in 1974, which recognized the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people,

- And the Casablanca Summit in 1989, which marked an important step toward Egypt’s reintegration into the Arab League and the advancement of efforts to resolve the Lebanese crisis.

In light of this analysis, it can be said that strengthening the role of Arab summits and qualitatively developing the Arab League is only possible through a transition from symbolic gestures and mere statements toward genuine partnership based on shared interests and effective political will. Only in this way can these summits be transformed into strategic platforms capable of producing actionable decisions that genuinely influence regional and international developments.