The majority of countries worldwide exhibit significant human diversity, reflected in population groups that differ from the dominant majority in their cultural, religious, or linguistic origins. This diversity, a hallmark of many modern societies, makes it challenging to envision a completely homogeneous society in terms of religion, language, or ethnic background.

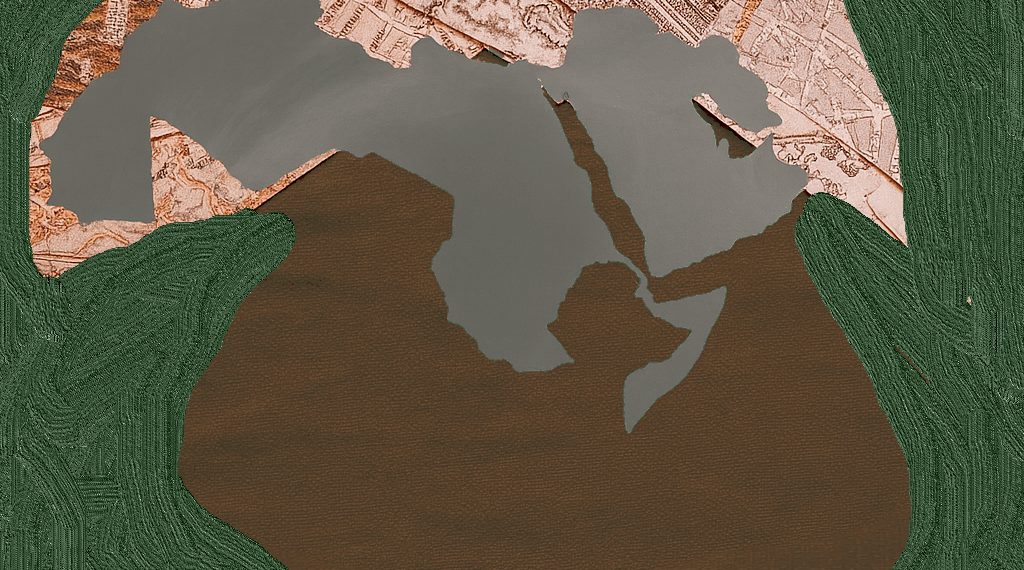

Religious conflicts in the modern world increasingly draw attention to the concerns of religious and ethnic minorities, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa, where ethnic and religious divisions intersect with the political boundaries of states. In efforts to strengthen national unity, some governments have introduced forms of cultural homogenization, overlooking the fact that societal diversity is a strength rather than a threat.

This approach, which ignores diversity or addresses it with integrative policies, often leads to negative outcomes, deepening feelings of marginalization among numerically smaller groups. Therefore, respect for diversity and its legal and political recognition is not merely an option but a necessity to ensure state stability and create more inclusive and equitable societies.

Definition of the Term “Minority”

In an academic context, the term “minority” is a multidimensional concept addressed across various fields, particularly political science, law, and sociology. Its evolution can be traced through definitions that reflect the diversity of theoretical and knowledge-based perspectives applied to it.

A political definition views a “minority” as a group or category of citizens in a specific country who differ from the majority in terms of gender, language, or religion. This definition highlights the political dimension, shedding light on identity differences within a country and the resulting challenges concerning belonging, citizenship, and representation.

In another context, the term “minority” is defined nationally as the portion of a country’s population belonging to an ethnic origin distinct from that of the majority. This definition underscores the close relationship between national identity and the concept of a minority, especially in multicultural and multiethnic states.

From the perspective of international law, a “minority” is defined as a population group differing from the majority in race, religion, or language, whether indigenous peoples or immigrant settlers, with full citizenship rights granted without discrimination. The state bears the responsibility to protect their rights. This definition emphasizes the state’s legal obligation to ensure equality in rights and freedoms, regardless of cultural, religious, or ethnic affiliations.

Some sources approach the term sociologically, defining a minority as any group that feels discriminated against or mistreated by the broader societal mainstream. This perspective focuses on the subjective and lived experience of minorities, highlighting feelings of inferiority or exclusion as a key factor in understanding their situation.

These varied definitions demonstrate that the term “minority” cannot be reduced to a single dimension but is a complex concept that must be examined from political, social, and legal perspectives. These perspectives also reveal that the minority issue is not merely a demographic phenomenon but a structural challenge concerning the organization of diversity within a state and the assurance of equal rights for all groups without discrimination.

Religious and Ethnic Minorities in the Arab World: Historical Contexts

Arab societies have been characterized by deep and rooted identity diversity since ancient times. The Middle East, due to its geographical location, has been a meeting point for various civilizations, cultures, and religions. As a key passageway for migrations and conquests, it became a site of continuous human exchange over thousands of years.

Although the Arab region is often labeled “Arab” due to the majority Arab population and the cultural dominance of the Arabic language, the reality reveals a diverse ethnic mosaic. Alongside Arabs, groups such as Kurds, Berbers, Armenians, Circassians, Black Africans, Nubians, Turkmen, and others exist. Some of these groups are not new or foreign but are integral to the region’s original history, predating Arab influence in some areas and making them indigenous peoples.

Diversity in the Arab world is not limited to ethnicity but also encompasses religious and sectarian diversity, with religions and sects sometimes intersecting with ethnic affiliations and sometimes existing independently. The perception of the Arab world as a monolithic Islamic space, whether in the past or present, is misleading. There is a significant presence of other religions, such as Christianity, with followers, particularly Copts in Egypt, numbering around ten million. Other sects, such as Sabians and Yazidis, are also present.

The term “minority” is relative and fluid. Not all groups classified as minorities are numerically small or new to the region. Some are authentic and deeply rooted, while others hold minority status only in specific geographical or demographic contexts. For example, Christians are a minority across the Arab world but form an influential part of Lebanon’s population. Shiites are a minority in many Arab countries but a majority in Iraq. Influence does not always depend on population size; Alawites in Syria, for instance, are a numerically small minority but governed the country for decades. Similarly, Berbers in the Maghreb, particularly in Algeria and Morocco, have a history predating Arab presence.

While this diversity could be a source of richness and strength, the prevailing attitude toward it in the Arab world—among governments, intellectuals, and religious leaders—is often one of mistrust and fear. Multiculturalism is frequently viewed as a problem or threat to be controlled rather than an opportunity to build richer, more tolerant societies. Official and cultural policies tend to enforce a uniform identity, whether ethnic, religious, or cultural.

Since the establishment of modern Arab states after World War I, this ethnic and religious diversity has not received adequate attention but has been either ignored or marginalized. With the rise of crises and civil wars in recent decades, particularly in countries with rich identity diversity, this neglect has become increasingly evident.

Religious and Ethnic Minorities in the Arab World: Political Dimensions

Until the early 20th century, the Middle East and North Africa formed a unified space within the Islamic world, where Muslims lived under a single governance system led by the Caliphate. With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I and the colonial division of its territories by Britain and France under colonial agreements, modern nation-states emerged in the Arab world. These new political entities, based on colonial considerations, were neither ethnically nor religiously homogeneous but included numerous minorities. The rise of Arab nationalism in these states led to tensions between the majority and minorities, tensions exacerbated by colonial powers to advance their strategic interests.

Despite a history of conflicts among rival forces, the region was characterized in most periods by relative openness to human and commercial exchange across its borders.

With the establishment of new states post-World War I, it was expected that these states would develop modern civic national identities and social and economic policies ensuring equitable equality for all citizens, fostering economic growth and prosperity. Such a civic identity forms the basis for state governance worldwide, paving the way to avoid conflicts that could undermine unity. However, most Arab states have achieved only limited success in this regard.

Immediately after their establishment, and even before full independence, two competing visions emerged regarding state-building and citizen identity: the Islamic vision and the secular-nationalist vision. Due to their core principles, both visions were far from promoting national unity or fostering a democratic, equitable state. In both cases, implementing these visions meant excluding minority groups from the majority’s political system.

The Islamic vision bases governance and social structure on Islam. The secular-nationalist Arab vision posits the state as founded on Arab citizenship—those whose mother tongue is Arabic and who consider Arab culture their own. For secular Arab nationalists, anyone meeting these criteria is accepted as a citizen with full rights, regardless of ethnic or religious origins. This ideology positioned Christians, widespread in various Arab countries and largely identifying as Arabs, as part of the majority society. However, this national vision left no room for ethnic or religious minorities to claim rights as distinct communities, as this contradicted the idea of nationalism.

In practice, a situation emerged where two forces interacted differently. In the initial phase after their establishment, the new Arab states sought to address the identity issue. The first constitutions, drafted in the 1920s and 1930s in Egypt, Syria, and Iraq under British and French influence, were relatively liberal, granting citizens equality regardless of religion—at least on paper. However, these constitutions emphasized that each state was part of the Arab nation, working toward its unity, with Islam as the state religion and Sharia as the source of legislation. These constitutions allowed the appointment of prime ministers who were not Sunni Muslims.

This relatively liberal spirit began to wane in the 1950s and 1960s as both visions failed to address the internal and external challenges of Arab states. Economies stagnated, and corruption was rampant. During this period, religious and nationalist ideologies spread across the Middle East. This led Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Sudan to change their governance systems under the pretext of addressing Arab societal issues. The new regimes promised modernization, economic and social reforms, and universal education. However, their inability to fulfill these promises soon became evident, and the states transformed into dictatorships.

The Solution to the Minority Issue in the Arab States

Despite the variety of perspectives and proposed solutions for the minority issue within the Arab nation-state, the most sustainable approach lies in the need for Arab states to develop a political culture that actively recognizes and respects cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity. Recognizing the rights of minorities and protecting their distinct characteristics, without jeopardizing state unity, is a fundamental prerequisite for promoting societal stability and preventing conflicts.

While current political conditions may not permit the formation of ethnically based parties—as seen in some European or Latin American countries—constitutional recognition of diversity, coupled with legal guarantees of religious freedom, provides a solid foundation for safeguarding minority rights. Promoting values such as tolerance and intercultural dialogue among different social groups contributes to a stable social order and strengthens national cohesion.

Movements advocating for ethnic minority rights, even if rooted in an ethnic perspective, are not contrary to democracy. On the contrary, they can be seen as a vital component of democratic development, as they enable the state to recognize the rights of part of its population and grant them full citizenship. The struggle of minorities for their cultural, political, and social rights actively contributes to democratic progress. Moreover, an individual’s connection to their ethnic identity within the state context is not always a threat to democracy but can be the only way for them to develop as an autonomous social actor. In some cases, ethnic identity can be a valuable tool for individuals to position themselves as active citizens capable of participating, negotiating, and protesting—helping them integrate more deeply into society and contribute to shaping the common good.